Sustainability Research: Reusing poultry waste

By Jane Robinson

Features Emerging Trends ResearchResearcher converts by-products into novel materials for industrial applications

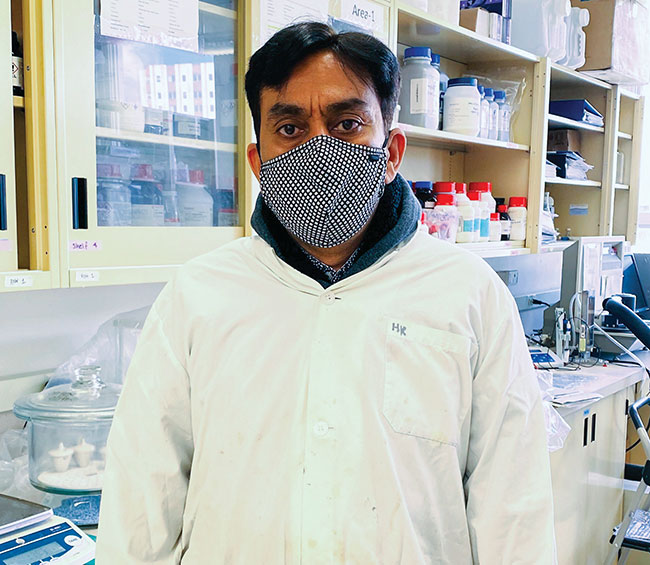

University of Alberta researcher Aman Ullah is focused on discovering ways to transform poultry by-products into innovative new materials. PHOTO CREDIT: Aman Ullah.

University of Alberta researcher Aman Ullah is focused on discovering ways to transform poultry by-products into innovative new materials. PHOTO CREDIT: Aman Ullah. Every year, the Canadian poultry industry produces 36 million spent hens and 240 million pounds of feathers. While most of these by-products are disposed of through incineration, composting or landfill, Aman Ullah is discovering ways to transform them into innovative new materials.

Ullah is an associate professor in the Department of Agriculture, Food & Nutritional Sciences at the University of Alberta. One of his main areas of research is developing novel materials from by-products that will divert waste from landfill while creating profitable new materials. And the Canadian poultry industry provides a steady source of raw material for him to work with.

Two of his current projects are using spent hens and chicken feathers to create a new biofilm for food packaging and a biosorbent that removes contaminants in oil sands wastewater.

The impetus for much of Ullah’s research is driven by the need to find new resources in a more bio-based economy with less dependence on fossil fuels. “Poultry by-products – that don’t have any other food or feed applications for animals or people – are a huge resource for new material development as high value chemicals, polymers and sorbents,” Ullah says.

Bio building blocks from spent hens

In his lab, Ullah extracted lipids (fats) and protein from spent hens using microwaves.

These components provided bio-based building blocks for materials, including bioepoxy that could replace soybean oil epoxy used in PVC and plastics production, biopolymers used in food packaging and monomers suitable for cosmetics and biofuels.

To bring these new biomaterials closer to commercialization, Ullah is part of a new spinoff company that will hopefully make some of these materials available in the next few years. “We will be looking to connect with producers as a source of spent hens when the company starts commercial production in the near future,” Ullah says.

Feather fibre improves water quality

Chicken feathers provide another valuable raw material for Ullah’s research. “Most of the chicken feathers produced every year in Canada end up in landfill,” Ullah says. By making structural changes to the fibres in the feathers, he’s created a biodegradable, ecofriendly keratin-based biofibre that holds great promise in water treatment. The biofibre from the feathers are the basis for a new biosorbent – a material that is able to remove contaminants from water.

“Keratin from poultry feathers is a unique material that has a lot of potential to remove multiple contaminants from water, using very low volumes of product. If we are able to remove metals, organics, pesticides and microbes in a single treatment – this is a technology that does not exist – it could be an important development for the poultry industry,” the researcher explains.

One of the initial uses for the new biosorbent is close at hand to Ullah’s lab in the Alberta oil sands. “Fresh water is used to extract bitumen but that water can’t be released or reused because of potential contaminants picked up in the process,” Ullah says. “Our new biosorbent could remove up to 90 per cent of metals in water.

“We have tested them on oil sands process affected water provided by the oil sand industry that is interested in the technology because of new regulations requiring more than 80 per cent of water to be recycled.”

Ullah is now working on larger scale trials to demonstrate how the powder-based biosorbent can help recover cleaner, recyclable water.

The water treatment technology also has potential for the poultry industry. “We did some initial work using the biosorbent with a poultry producer in Alberta and are now looking at modifying the keratin material in feathers to be able to remove pathogens from drinking water in poultry barns,” Ullah explains. “Our target is to make a single treatment technology using feathers to remove metals, organics, pesticides and microbes from drinking water.”

Dealing with Deadstock: Streamlining on-farm composting

While Aman Ullah is transforming micromaterials from spent hens and chicken feathers into novel bio-based materials, two Canadian manufacturers continue to innovate on-farm composters to efficiently and safely transform deadstock into valuable field nutrients.

For the past 10 years, Lucknow Products have been manufacturing and distributing the Green Machine – a fully enclosed, self-mixing compost machine – from its Ontario location. The company has been making TMR mixers since 1980, and a new customer approached them about modifying the feed mixer specifically for poultry composting.

“The Green Machine is a very slow rotating horizontal four auger mixer that combines deadstock with wood shavings for active decomposition in just a few days,” says Jim Cranston, one of the owners of Lucknow Products. “Under ideal conditions, after all deadstock has been added, you have nothing left but nutrient rich compost within 72 hours.”

Augers are timed to regularly turn material, allowing oxygen pockets formed from the wood chips to move throughout the mixer and speed up the decomposition process. Composted material can be stockpiled in open air until it can be applied to crop land.

The stainless steel units are coated in foam insulation to keep internal temperatures up, and are currently used mostly in regions of Canada and the U.S. where warmer temperatures naturally aid in decomposition. “We are looking at adding a heated cord in the walls of the unit so it can be plugged in for use in cooler regions,” Cranston says.

In Western Canada, another local business continues to lead the in-vessel compost market with its Biovator. Based in Swan Lake, Man., Biovator is designed, manufactured and distributed internationally through Nioex – a family owned business operated by Steven Sierens, his brother Derek and father Dan. The composter technology is used for deadstock as well composting organic waste from restaurants, zoos and abattoirs.

The Biovator uses deadstock and a carbon source – wood chips – to create nutrient rich compost. Deadstock can be loaded daily, as needed, into one end of the long, insulated stainless steel unit. Timed revolutions and paddles then work to aerate and break up material, constantly pushing mature material down the vessel towards the end where compost is removed. Mixing frequency is based on the volume inside the unit.

“The Biovator efficiently regulates the internal temperature for optimal decomposition that means material is digested into compost within three weeks,” says Steven Sierens, who’s in charge of business development. “One of newest models has the addition of remote-control hydraulics, making it much easier for daily loading of deadstock into the unit.”

Print this page